Leaving the theater after National Anthem, I overheard a young man (in his 20s maybe?) say “I think that was the best movie I’ve seen this year.” Then he added, “It’s not been a great movie year.”

Was it movie snobbery? Maybe. National Anthem is a unique experience, so gutsy and heartfelt that it short-circuits conventional movie criticism.

Was it latent homophobia? He was with two young women, and he seemed pretty straight. But he was there, and clearly enjoyed it. And oh boy, National Anthem sure enough demands self-reflection. Watching it as a straight person – or questioning person – is sure to be a mind-fuck.

I had qualms of my own, for sure. Early on in the film – when the gang from Splendor descends on a local tractor supply store – I leaned over to my partner and said “These people are all way too pretty to be on a ranch in New Mexico.” That wasn’t a complaint, just an observation. Because goddamn, this movie is full of pretty people.

Is National Anthem the Best Film of the Year?

So was our fellow movie-goer right? National Anthem checks all the boxes of a great film – gorgeously photographed, thematically ambitious, exquisitely acted, precisely written. It’s tight but not airtight, sparse but not bare, patient but not slow.

Is it the best movie I’ve seen this year? Personal opinion, yes, so far. More importantly, though, it’s the movie I most needed to see. One that, in this horrorshow year of democracy on fire, affirms love and beauty and actual freedom – the hard-won kind that takes sacrifice and empathy, not the kind based on oppressing the people you hate.

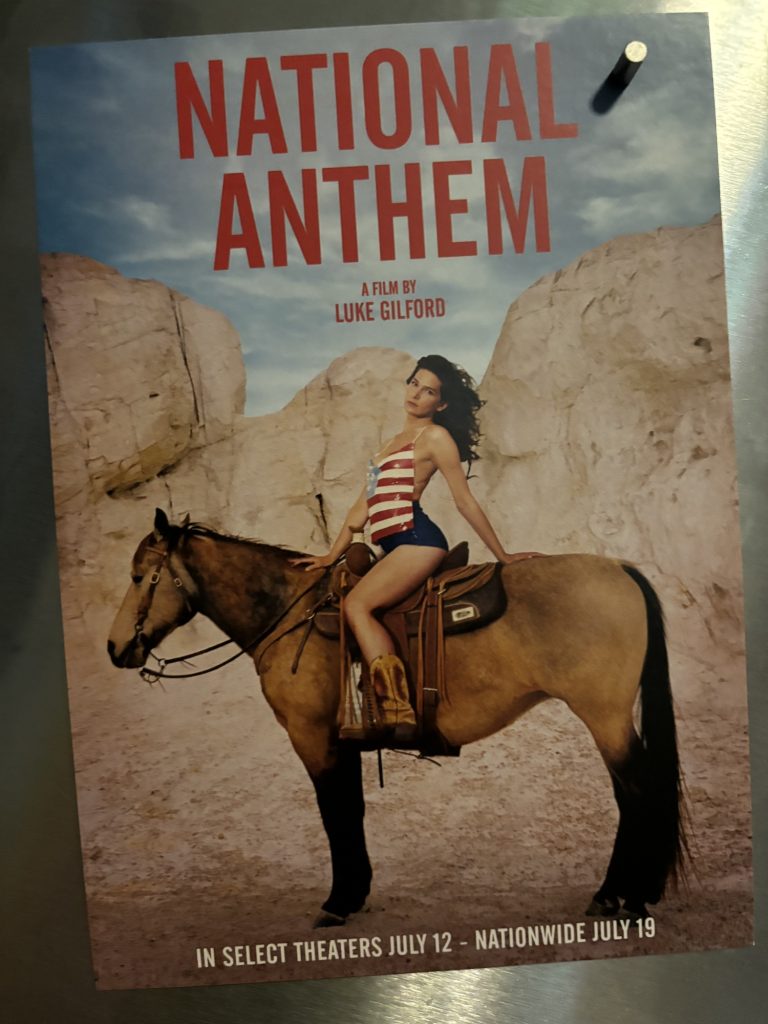

Inspired by his 2020 photographic project documenting queer rodeo, writer-director Luke Gilford has created a vibrant, immersive experience in his first feature film. Lead Charlie Plummer plays Dylan, a white working-class 21-year-old who lives with his alcoholic hairdresser mother and his little brother. Dylan works as a day laborer to support the family, standing outside the feed store waiting for whatever pickup truck will bring him somewhere to break his back in the New Mexico sun.

In this horrorshow year of democracy on fire, [National Anthem] affirms love and beauty and actual freedom – the hard-won kind that takes sacrifice and empathy.

Dylan’s life changes when Pepe (Rene Rosado) picks him up to mend fences and hoist hay bales at the House of Splendor, a ranch unlike any Dylan has ever seen. Surrounded by a multi-racial crew representing every letter of LGBTQ+, a day’s work turns into weeks, and a tentative place in the family, while Dylan falls hard for Pepe’s partner Sky (Eve Lindley).

There’s no better place to interrogate the complexities of gender and sexuality than in Southwest cowboy culture – the most American of American settings, the place where the myths of manhood and self-reliance and liberation have played out for half of America’s history. Gilford said in an interview that he wanted to depict “A cowboy who’s brave enough to love and be vulnerable and be soft and tender. But to also ride a bull.”

National Anthem isn’t looking for a wide reach. It’s a movie made by queer people, for queer people. There is no hand-holding for straight folks. Nobody debates pronouns. No one explains the intricacies of polyamory. Nobody gives a dissertation on the meaning of drag in queer history. The closest you get to a lesson comes when two drag queens call Dylan “Trade of the season” and Sky says quickly, “They think you’re cute” as she hustles him away.

Like Dylan, the audience gets swept into the House of Splendor. Inspired by quiet, observational films like Paris, Texas, Gilford’s camera lingers – over landscapes, over faces, over buildings, over bodies. Around us, the characters live and behave.

Oscar-Worthy Acting (Not That the Academy Will Notice)

Dylan’s awakening is portrayed almost entirely visually – part Gilford’s direction, part Plummer’s acting. True to the character, Plummer doesn’t talk much; he takes it all in, and Plummer shows Dylan taking it all in.

A few critics have complained about Plummer’s subdued performance, but they obviously weren’t watching the same movie I watched. Plummer acts like the silent screen stars. It’s the best acting an actor can do, to show a character’s mind working behind his eyes.

On the topic of acting: I’m not the only one saying it, but I can’t say it enough – Mason Alexander Park, best known for Sandman and the new Quantum Leap, walks away with the film. As Carrie, Park provides a calm center to hang on to in the swirl of big emotions. Every scene Carrie appears in, they bring love, humor, and wisdom. They don’t need a big dramatic monologue – throughout the film, Park’s expressive face and body language do the work. The lesson: find someone who looks at you the way Mason Alexander Park looks at anything

Park also gets the funniest line in the movie. Trying to adjust a wig on Dylan’s head, with the desert wind wreaking havoc, Park mutters “This wind is so transphobic” – an ad-lib that director Gilford immediately knew had to go into the final cut. In Park’s delivery, the line comes across as true to life and genuinely weary. I don’t think everybody caught it. It barely registered in the sound mix, and could easily have been a throw-away. But the scattered bursts of laughter told you who was really tuned into the movie.

Family, Found Family, and Empathy

There’s another element that deserves mention, especially coming to the movie as a middle-aged person. Coming-of-age and self-discovery movies usually assume that the main character is essentially free. They might have something holding them back – the family business, their social class – but usually the only thing really holding them back is themself.

Dylan is not free. His mother and brother depend on him. He knows it. Gilford knows it. The movie knows it.

Dylan’s dream is to save up enough money to buy a used RV and run away from it all. But in the meantime, he still has to make sure his little brother gets his medicine and has food to eat, and that his mother doesn’t spend all their money drinking.

In other words, Dylan has adult responsibilities even as he is discovering himself. His sense of responsibility adds poignancy to the movie. He cannot be wild and free. He cannot run away from his brother, or even his mother.

Robyn Lively, as Dylan’s mother, Fiona, brings richness to an underwritten character. Her performance interrogates the “bad mother” cliches that put a gross, misogynistic stain on similar stories. And Joey DeLeon, who plays Dylan’s brother Cassidy, is the most delightful little kid I’ve seen in a movie in a long time. Without a single bit of show-biz-kid phoniness, Cassidy has his own mini-coming-of-age as Dylan and friends bring him to a western drag show, buy him his first dress, and give him a glimpse of the world that will soon open to him.

The emphasis on family, Gilford says, was important. Most queer movies center on finding the chosen family, but Gilford wants a multi-faceted view: “Coming to terms with and healing the connection to the biological family.” The theme of most queer movies, he jokes, is, “Too bad about your biological family, Happy Pride.” But he wanted to show how, with Fiona, “Even the proximity to this community opens her heart, opens her mind.”

Park says in an interview, “I think that art is an empathy machine.” There’s no better description for National Anthem. National Anthem brings empathy to all of the characters, in all their complexities and dissonances – Pepe’s generosity and his jealousy; Fiona’s bitterness and her soulfulness. As Gilford says, he intended to create a “western for the new world.” Let’s hope he’s right – because it’s a world that has enough room for everybody.

Related: